On March 8th, 1965, the 4,000 strong 9th Marine

Expeditionary Brigade (9th MEB) landed at Da Nang, the first elements of the

USMC to be sent officially into combat in South Vietnam. (A number of Marine

units, including air defence elements, transport helicopters, engineers, and

Company D, 1st Battalion, 3rd Marine Regiment were already there, but March 8th

is the official date). The 9th MEB were committed to ensure the safety of the

Army, Air Force, and Marine aviation units that were already based at Da Nang.

After a perimeter around Da Nang was secured, additional landings were made at

Chu Lai, and other enclaves along the coast in I Corps, again with the purpose

of securing enclaves to operate aviation elements. By May, the number of

Marines ashore in Vietnam had risen to 17,000, and IIIrd Marine

Expeditionary/Amphibious Force was established to control the Marine units in

Vietnam. (It was decided that the term 'expeditionary' smacked a bit too much

of the now departed French, so that term was officially dropped). The 1st

Marine Air Wing was set up to control all Marine aviation elements in country,

and Marine strength totaled some 25,000 by the end of July.

The Marine ground units had been restricted to

operating in the immediate area about the air bases, and were not allowed to

move out and engage the Viet Cong. After the 1st Viet Cong Regiment had won an

impressive string of victories against the ARVN forces in the area south of Chi

Lai in the summer of 1965, the Marines stationed there were given permission to

move out of their defensive perimeter and engage the enemy. The stage was set

for Operation Satellite. (Unfortunately, the power failed while the operations

order was being typed, and it was completed by candlelight. The clerk misread

Starlite for Satellite, and so typed that throughout the order). The plan for Satellite/Starlite was as follows;

Headquarters, 7th Marines, along with elements

of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines (3/3), would board the transports in Chu Lai

that had just brought the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (1/7) there. This force

would sail south, hoping to rendezvous with the 7th Fleets Special Landing

Force, on which the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines (3/7) was embarked. (The Special

Landing Force was off station at the moment, and was on a high speed run back

to Vietnam from Subic Bay. It remained to be seen if they would arrive in

time). The 3/3/ Marines would arrive off An Cuong 1 on the morning of the 18th,

and land on the beach there at 0630 and drive inland.

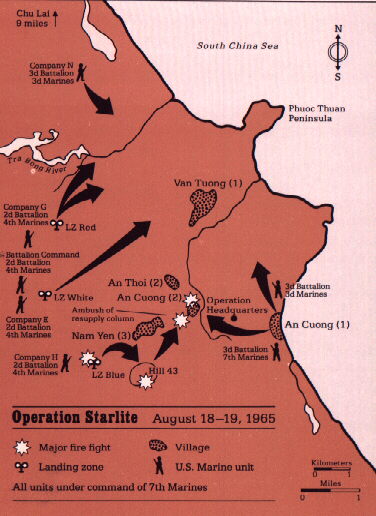

The 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines (2/4), would be

lifted by the helicopters of the Marine Squadrons 161, 261 and 361 into the

LZ's Red, White and Blue at the same time. The 2/4 would drive for the coast,

linking up with the main body of the 3/3. To the north, Company M, of the 3/3,

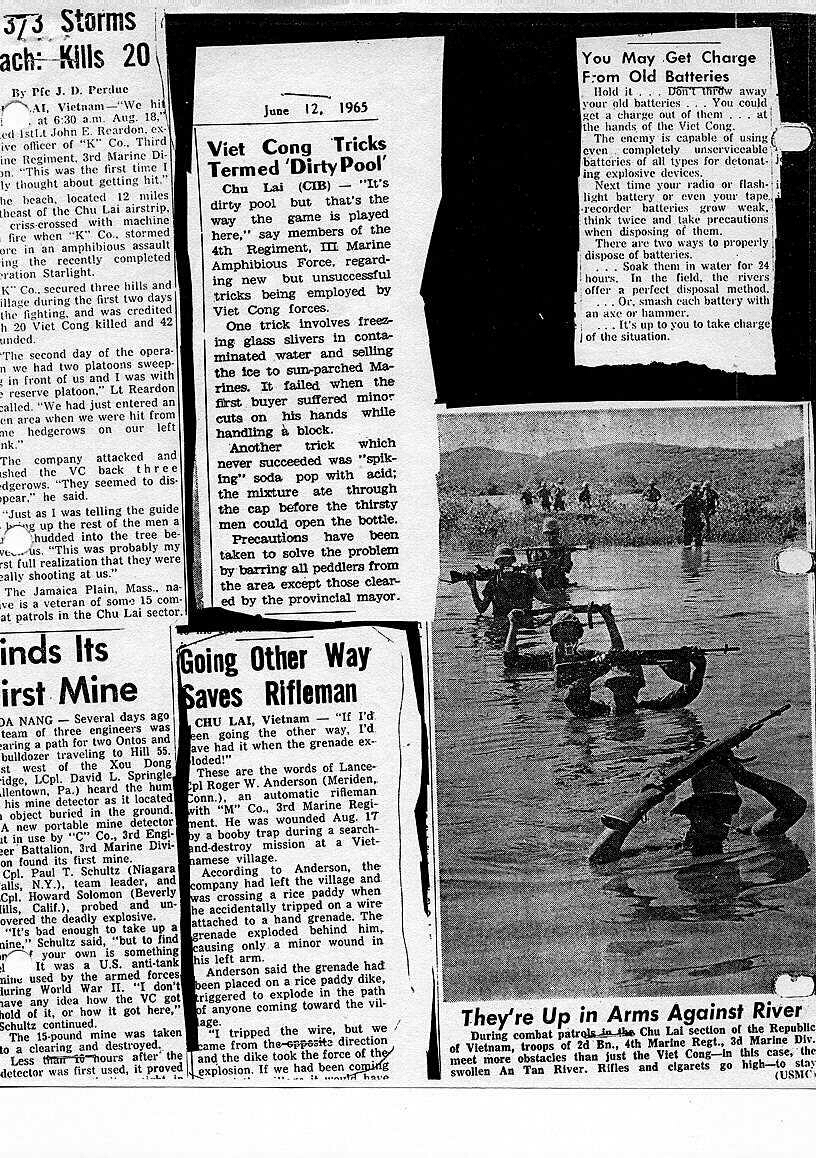

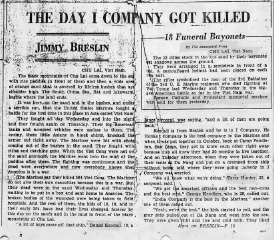

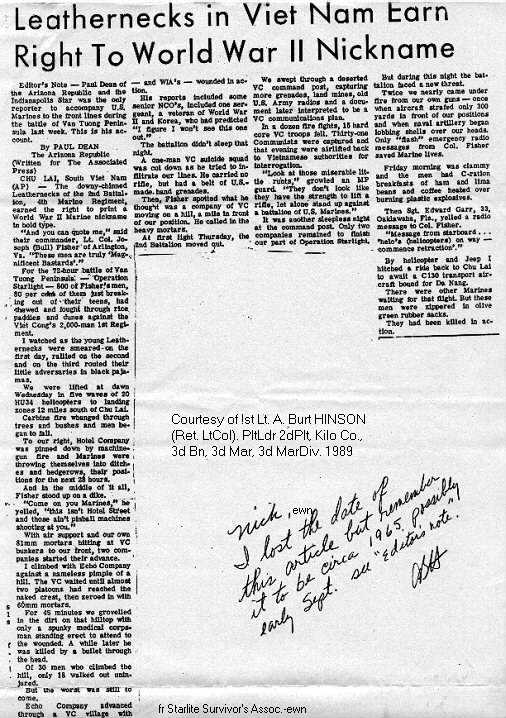

would move south to secure the Tra Bong River. Operation Starlite (August 1965) was the first large-scale US ground operation in Vietnam. The target of the operation was the 1st Viet Cong Regiment, reported to be at a strength of about 1,500 men, that had been located in the Van Tuong village complex. The attack force was under the command of the 7th Marines and consisted of the 2d Battalion, 4th Marines and the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines from Chu Lai, and the 1st and 3d Battalions of the 7th Marines from the Special Landing Force. Starlite began on August 18, 1965, with 2/4 and 3/3 leading the dawn attack. The 3d Battalion, 7th Marines landed by helicopter and over the beach later that day; 1/7 joined the operation on August 20. At the completion of Operation Starlite on August 24, 1965, 613 Viet Cong had been killed at the cost of 17 Marines killed and 203 wounded. This below illustration is from "US Marines in Vietnam, the Landing and the Buildup, 1965" Jack Shulimson and Major Charles M. Johnson, USMC, History and Museums Division, Headquarters, US Marine Corps, Washington, DC, 1978.

On August 15 the marines received their first break. A deserter from the Vietcong 1st Regiment in-formed General Thi of a major build-up of enemy Maine Force units in the Van Tuong village complex, twelve miles southeast of Chu Lai along the coast. The VC goal was to achieve a great psychological victory by surprising the isolated marine base at Chu Lai in the first major engagement between American and enemy forces. Marines rush a wounded Veitcong prisoner-one of more than one hundred captured in Starlite to a Huey helicopter. Operation Starlite General Thi, informing none of his own subordinates, immediately relayed the information to General Walt. Marine intelligence had by this time received sufficient evidence on its own to corroborate the deserter's story. Colonel Edwin Simmons, newly arrived operations officer for III MAF, recommended a "spoiling attack" to prevent the anticipated VC strike against Chu Lal. The timing was fortuitous. The arrival of reinforcements at the Chu Lai base on August 14 enabled Walt to reassign two experienced combat battalions, 2d Battalion of the 4th Marines (or 2/4), and 3d Battalion, 3d Marines (3/3) to the command of Colonel Oscar F. Peatross, commander of the 7th Marines. In addition, another marine battalion, afloat offshore, served as a reserve force that could be thrown into the battle when and where necessary. Finally, two U.S. Navy ships in the area, the U.S.S. Galveston and U.S.S. Cabildo, could provide offshore fire support. The operation, code-named Starlite, would be a classic marine encounter, combining land and sea forces, including an amphibious landing and coordination with the navy. It would be a very different battle for the Vietcong, accustomed to fighting with their backs to the sea, knowing that against South Vietnamese forces the water could always be used as an avenue of escape. , Operation Conducting an aerial reconnaissance of the operational area, which was about ten miles south of Chu Lai, Colonel Peatross found that the terrain was dominated by sandy flats, broken by numerous streams and an occasional wooded knoll. The scattered hamlets possessed paddy areas and dry crop fields. While airborne, Peatross selected the assault beach as well as three landing zones among the sand flats, about one mile inland from the coast. Operation Operation Starlite began inauspiciously at 10:00 A.M. on August 17, when Company M of the 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, took a short ride south of Chu Lai before marching four miles farther south and camping for the night just north of Van Tuong. They met only light resistance and, since marine patrols in the area had been frequent, aroused no suspicion. Seven hours after Company M departed, the rest of the 3/3 and the command group embarked on three amphibious ships which, after a decoy maneuver, arrived in the area of the landing beach at five in the morning of August 18. Fifteen minutes before the 6:30 A.M. H-hour, marine artillery and jets began to pound the three landing zones west of Van Tuong, LZ Red, LZ White, and LZ Blue (see map). Eighteen tons of bombs and napalm were dropped, adding to the firing of 155MM guns. At H-hour the troops of the 3/3 began their beach assault and pushed inland as planned. At 6:45 A.M. Company G of the 2/4 landed at LZ Red, while Company E landed at LZ White and Company H landed at LZ Blue forty-live minutes later. The 3/3 approached Van Tuong from the south, while companies E, G, and H of 2/4 were to move in from the west. Company M blocked any retreat to the north by the VC, and the navy ships prevented an escape to the east via the South China Sea. Van Tuong and the Vietcong were surrounded. For the most part, the marines met little resistance as they closed in, but fierce fighting broke out near LZ Blue. Operation In the VietNam War, intelligence was never precis and Company H had landed right in the middle of the Vietcong 60th Battalion and found itself surrounded. The VC let the first helicopters land without incident, then opened up on succeeding waves, a tactic they had used successfully against ARVN. Three U.S. Army UH-lB helicopter gun ships were called in to strafe the VC strong hold, a small knoll just east of LZ Blue called Hill 43. (Hill were given numerical distinctions according to the height in meters.) Meanwhile the infantry protected the LZ until the full company had landed. Company H commander, First Lieutenant Homer K. Jenkins, ordered an assault on the hill by one platoon, but it quickly stalled. Regrouping his men, and realizing that he had happened upon a heavy concentration of VC, Jenkins ordered in strikes against Hill 43 and then assaulted it with all three of his platoons. Reinforced by close air support and the marines overran the enemy position, claiming six KIA at one machine-gun position alone. Hill 43 was taken. Operation Heavy fighting also took place in the village of An Cuong (2)-approximately two miles northeast of Hill 43 when two platoons of Company I attempted to clear the village of enemy snipers. After an initial setback, the company's reserve platoon was thrown into battle and the troops cleared the village. Company I's commander, Captain Bruce D. Webb, was among those killed in the early fire, and his company executive officer, First Lieutenant Richard M. Purnell, assumed command of the successful counter assault. Purnell counted over fifty enemy bodies when the fighting ended. One Company I squad leader, Corporal Robert E. O'Malley, single-handedly killed eight Vietcong that day and became the first marine to win the Medal of Honor in VietNam. (Later, a posthumous award was made to Captain Frank S. Reasoner, killed in action in July.) Operation The most dramatic fighting of the day was the result of another favorite VC tactic :ambushing a relief column. between 11:00 AM. and noon Major Andrew G. Comer sent a resupply column to aid beleaguered Company I. The column, which included three flame tanks, the only tactical fire support available, quickly lost its way. Suddenly, VC recoilless rifle fire and a barrage of mortar rounds rendered the tanks useless in providing fire support. Using only their small arms, the entrapped marines attempted to hold the advancing VC infantry. The marine radio operator panicked and, according to Major Comer, "kept the microphone button depressed the entire time and pleaded for help. We were unable to quiet him sufficiently to gain essential information as to their location." Finally Comer organized a rescue mission, led by the already exhausted Company I and including the only available M48 tank. By luck, one of the trapped flame tanks managed to break through the VC infantry and return to Comer's command post. The crew chief was able to lead the rescue mission to the location of the column. Approaching the besieged supply column, the relief force quickly drew heavy fire. Recoilless rifle fire knocked out the M48. Within minutes five marines lay dead and seventeen wounded. Comer called for artillery fire and air support, and enemy fire soon sub-sided. As Comer put it, "It was obvious that the VC were deeply dug in, and emerged above ground when we presented them with an opportunity and withdrew whenever we retaliated or threatened them." Operation The heavy fighting of the first day proved to be the only major contact of the seven-day operation. For Companies H and l it had been an exhausting time. Together the two companies had sustained casualties amounting to over 100 of their original 350 men, including 29 dead, but in return they claimed 281 VC dead. Operation On August 19, Starlite's second day, sporadic and isolated fire came from enemy soldiers covering their main force's retreat, but organized resistance had ended. The operation extended for five more days with the Marines, now joined by ARVN troops, conducting village-by-village searches. At its conclusion the marines could claim 573 confirmed enemy dead and 115 estimated, while suffering 46 deaths themselves and 204 wounded. The battle had been won by overwhelming American firepower. Artillery support from Chu Lai had fired over three thousand rounds while the navy ships had supported the infantry with 1,562 rounds, sunk seven sampans apparently carrying fleeing VC, and pinned down one hundred enemy soldiers attempting to escape from the beach. Moreover, the Marines had benefitted from the close coordination of tactical air power, a coordination that ARVN never seemed to achieve. General Walt later commented that air support was used "within 200 feet of our pinned down troops and was a very important factor in our winning the battle. I have never seen a finer example of close air support." The marines had won by doing what American troops do best coordinating their firepower on land, sea, and air. But most important, the marines had learned at least one valuable lesson from Starlite. Operation At General Thi's insistence no ARVN commander was even aware of the planned operation. At the last moment General Hoang Xuan Lam, whose men augmented the marines during the second day of operations, was in formed of his role. Even American reporters did not arrive on the scene until the second day. As a result the VC were caught by total surprise. Future operations, similar in nature to Starlite, were much less successful. For political reasons the Marines had to inform ARVN of future operational plans and there by risk the likelihood of this knowledge somehow reaching the enemy. Operation The experience taught many minor lessons as well. The planned ration of two gallons of water per man each was insufficient in the heat of Vietnam. The M14 automatic rifle proved too heavy and bulky, especially for support troops who often crammed into small personnel carriers and the search began for a lighter, more maneuverable basic weapon. Operation Finally, for the Marines the operation dramatized the complexity of fighting a war among civilians. Publicly the Marines declared that only fortified enemy villages were destroyed, but the official "after-action" report stated: "Instances were noted where villages were severely dam aged or destroyed by napalm or naval gunfire, where the military necessity of doing so was dubious." Operation Perhaps the most important outcome of Operation Star lite was its psychological lift. In the first major engagement between American troops and Main Force Vietcong soldiers the Americans had been victorious. Had the American forces lost-a real possibility given their in experience-the effects might have been severe indeed The old tactics of the VC, which had worked so well against ARVN, failed to rout the Marines. So the enemy learned a lesson as well; it would be many months before they would again stand to fight against the Marines Operation For the Marines, Starlite, or the Battle of Chu Lai as became known in their lore, took on an almost mythic' importance. For those marines who came later and for, whom the landings at Iwo Jima and Inchon Beach were the glory of another generation, the Battle of Chu Lai remained for many months the only evidence of what the marines could do if the enemy stood and engaged.

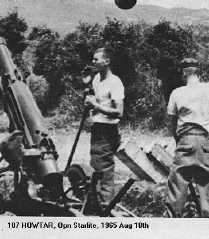

The source of this Information was the: History of Vietnam & The Vietnam War web page for HMM-161 USS PRINCETON USS IWO JIMA 4 MARINES For date 650507 HMM-161 was a US Marine Corps unit USS PRINCETON was a US Navy unit USS IWO JIMA was a US Navy unit 4 MARINES was a US Marine Corps unit Primary service involved, US Marine Corps Quang Tin Province, I Corps, South Vietnam Location, Chu Lai Description: As part of the amphibious landings at Chu Lai, elements of the 1st Battalion and 2d Battalion, 4th Marines landed over RED Beach. After landing, they moved approximately three miles inland to secure LZ ROBIN which overlooked Route 1. HMM-161 lifted two companies from the 1/4th Marines from the USS Princeton onto ROBIN as part of RLT-4. Later in the day, the Navy substituted amphibious assault ships and HMM-161 relocated to the USS Iwo Jima to continue supporting the Chu Lai landings. The troops met no resistance and occupies their planned objectives. Elements of the 2nd ARVN Division had been operating in the area for security reasons since earlier in the month. By the end of the first day, the 4th Marines defensive postions extended in an irregular arc from the Ky Ha Peninsula in the north, to the high ground in the west, and from there seaward to a point three miles south of RED Beach Comments: LTC Morrison, Gene W.; HMM-161 CO; The source of this information was USMC 1965 History P:29+ Battle of Chu Lai: the Main Force Viet Cong were poised for an attack on Chu Lai in August 1965, but their plans \were foiled in a "spoiling attack" by Marines in what would be the first major U.S. battle of the Vietnam War. (Deadliest Vietnam Battles) VFW Magazine, Oct, 2003, by Al Hemingway Gen. Lewis W. "Silent Lew" Walt, commanding general of the III MAF (Marine Amphibious Force), was in a quandary. Intelligence revealed that the 1st VC (Viet Cong) Regiment was massing for an assault on the airfield at Chu Lai, South Vietnam. Chu Lai, situated on the coast, was located in the southern I Corps region of the country. Walt discussed his options with his staff and finally decided to strike the enemy in their stronghold on the Van Tuong Peninsula, approximately nine miles south of Chu Lai itself. It was a daring plan since it would leave the airstrip defenses weakened. Walt, however, felt the gamble was worth it. Starlite is Born Col. Oscar Peatross, 7th Marine Regiment commander, was in charge of the operation, which was dubbed Starlite. He opted for a two-pronged strike at the VC. He selected the 3rd Bn., 3rd Marines, for the amphibious assault and 2nd Bn., 4th Marines, for the helicopter strike. "The proposed battleground was mostly rolling country," Peatross later wrote, "about three-quarters cultivated, and elsewhere there was thick scrub [spread] from six to 100 feet ... and there were few rice paddies. The beaches were sandy, with dunes in some places as far inland as 200 yards." The 3rd would come ashore on Green Beach just north of the village of An Cuong No. 1; the 4th would be choppered into three landing zones (LZs) named Red, White and Blue. Terrifying Moments Just after 6 a.m. on Aug. 18, 1965, K Btry., 4th Bn., 12th Marines, fired the opening salvo of the battle for Chu Lai. As the 155mm shells pounded VC positions, the destroyers USS Orleck and Prichett, and the heavy cruiser USS Galveston, let loose a barrage on the enemy. In addition, fighter aircraft from Marine Air Groups (MAG) 11 and 12 dropped 18 tons of ordnance to soften the enemy's bulwarks. After the preparatory bombardment, the 3rd Bn., 3rd Marines, made its way ashore and quickly moved inland. As the village of An Cuong 1 was secured, I Company set out to take An Cuong 2 and link up with the 2nd Bn., 4th Marines. The "Magnificent Bastards" of the 2nd Battalion would find the going much tougher than originally thought. E Company soon found itself fighting a well-entrenched enemy on a ridgeline near the LZ. A forward observer spotted more than 100 VC moving into the open. He quickly called for a 107mm "Howtar"--a 4.2-inch mortar mounted on a 75mm howitzer frame. The unique weapon was swung into action and within minutes more than 90 VC soldiers were killed. Meanwhile, UH-34Ds from Helicopter Marine Medium (HMM) Squadrons 261 and 361 began touching down on LZ Blue. As H Company Marines leaped from the aircraft, the enemy hit them with withering fire from atop Hill 43, a small knoll southeast of the LZ. The first few moments were terrifying. A helicopter door gunner had his jaw torn apart from enemy fire. One Marine was struck in the throat. Another stumbled and fell with a huge wound in his stomach. "You just have to close your eyes and drop down to the deck" said Capt. Howard Henry, a chopper pilot with HMM-361. 'All Hell Broke Loose' Unknown to the Marines, H Company had landed atop the headquarters of the 60th VC Battalion. 1st Lt. Homer Jenkins, company commander, quickly organized his men to assault Hill 43 and eliminate the threat. Skyhawks and Phantoms from Fighter Squadrons 513 and 342 hammered the hilltop as the infantrymen pushed forward. Assisted by M-48 tanks, the Marines soon dislodged the VC from Hill 43. While Hill 43 was being cleared, I Co., 3rd Bn., was inching its way toward An Cuong 2. The hamlet consisted of 25-30 huts, fighting holes and camouflaged trench lines connected by a system of interlocking tunnels. As the Leathernecks moved cautiously into the village, a grenade killed Capt. Bruce Webb, the company commander, instantly. He was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for his extraordinary heroism that day. "I was there when Capt. Webb got killed," said Sgt. Dwight Layman. "A gook threw a grenade into the command group. It also killed the radio operator. I immediately grabbed an incendiary grenade and tossed it into the spider hole and fried him. I was setting up LZs for the choppers to evacuate the wounded when a round caught me in the back of the neck and went out through my shoulder. That was it for me. My part in Starlite was over." But before the riflemen could secure An Cuong 2, they were told to reinforce K Company, which was engaged in a heavy firefight about 2,000 meters to the northeast. H Company was moving on An Cuong 2 to meet up with I Company. As they approached the tiny village of Nam Yen 3, it was decided to bypass it and keep going. Without warning, the company was struck with intense automatic weapons fire. An open area between the villages was strewn with spider holes and machine gun nests hidden in grass huts. "As we came nearer, snipers opened up and then all of a sudden all hell broke loose," remarked Sgt. Victor Nunez of Weapons Platoon. "It seemed a whole damned division of VC was out there waiting for us. Those bastards had us zeroed in [with] machine guns, mortars, recoilless rifles and rocket-propelled grenades. I saw a lot of our guys get hit ... our company Gunny was killed also." Pfc. Paul Meeters was serving with the Anti-Tank Plt., H & S Co., 3rd. Bn., 7th Marines, when he was called off a helicopter carrier to engage the enemy. He remembers "almost buying the farm" at Van Tang. "We went into the village and received fire from the huts, but as we cleared each hut, fire came from behind us. We later learned the ville was honeycombed with tunnels." Fierce Fighting As medevac choppers tried desperately to land, Lance Cpl. Joe Paul, a "baby faced" 19-year-old fire team leader, positioned himself between the helicopters and the enemy. As he laid down covering fire, wounded Marines were placed aboard the aircraft for evacuation. Unfortunately, Paul was struck several times and died. He was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. The fighting was fierce. Lance Cpl. Ernie Wallace saw enemy soldiers hidden behind hedgerows. He screamed: "Start killing trees? He began delivering accurate fire at the treeline nearby, killing some 25 VC in the process. His keen observation saved the lives of his fellow Marines. He, too, was awarded a Navy Cross. Cpl. Robert O'Malley of I Company eliminated an enemy position and was a source of inspiration to his fellow Leathernecks. Although wounded three times, he would not permit himself to be evacuated until all of his squad was aboard the helicopter. He and Paul were the first Marines to be awarded the Medal of Honor for Vietnam. Squeezing the Vice Soon, elements from the 3rd Bn., 7th Marines, were landing to reinforce the assault battalions. As the additional rifle companies came ashore, the enemy quickly departed the area. Starlite, though, would last another five days as the riflemen combed the area, eliminating VC spider holes they encountered. The Marine units pushed eastward to "squeeze the vise" around the VC and drive them toward the sea. In the end, 614 VC were confirmed killed. The Marines also took nine prisoners and confiscated 109 assorted weapons. The Leathernecks sustained 45 dead and 203 wounded. By all counts, Starlite was a success. The Marines had thwarted a major attack against Chu Lai. But despite their battering, the tenacious 1st VC Regiment would return to fight another day. AL HEMINGWAY, a Marine Vietnam vet, has written extensively on the war. NOTE: This is the first article in VFW's Vietnam War series. Personal accounts from the battles requested in the June/July 2003 issue, p. 8, are still needed for upcoming stories. COPYRIGHT 2003 Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States

Click on the Picture to view at full size

Main Page |